Over the course of my time spent in the photography MFA program, I have been exposed to hundreds of photographers. Reviewing the beliefs and inspirations helped me to consciously and subconsciously frame and improve my own notions around art. Early within my studies, the main focus included proper technique, composition, formal elements, and narrative. The following questions were pertinent to my studies:

· How was the photograph created?

· What equipment and techniques were used?

· How did the photographer use compositional elements to strengthen the image’s aesthetic qualities and narrative meanings?

As I advanced through the MFA program, I was asked to answer these next questions:

· Why was the photograph made?

· Did the photographer apply a unique personal vision to the work?

· Do I feel the photograph is effective given the intended audience and application?

As I’m rounding the bases and heading home (aka: graduation), I’m learning that it’s necessary to examine both the photograph and the drive behind the photographers who create them. Now, it is time to consider the following:

· Who is the photographer, and what is his or her background?

· What is the photographer’s motivation and inspiration as an artist?

· What defines the photographer’s signature style over multiple bodies of work?

· Would I identify the photographer from seeing the work?

· What is the underlying message that I feel the photographer is conveying through his or her greater body of work?

"The study of photographs at an advanced level is not just about looking; it is about paying attention to what lies beneath the surface of the photograph. By examining the interests, motivations, and intentions of the artist, you can begin to see the psychological and philosophical factors that drive their work. There is little or no separation between a meaningful piece of art and the artist who made it."[1]

While considering the motivations and inspiration behind my series, Blue Pencils, I can’t help but recall the weeks and months after losing a dear friend a couple of years ago. Bret’s sudden passing was the third friend my husband and I had lost in the short span of a few months. At the time, I was working on an entirely different fine art series, which was a strong contender for my final thesis proposal in the MFA program.

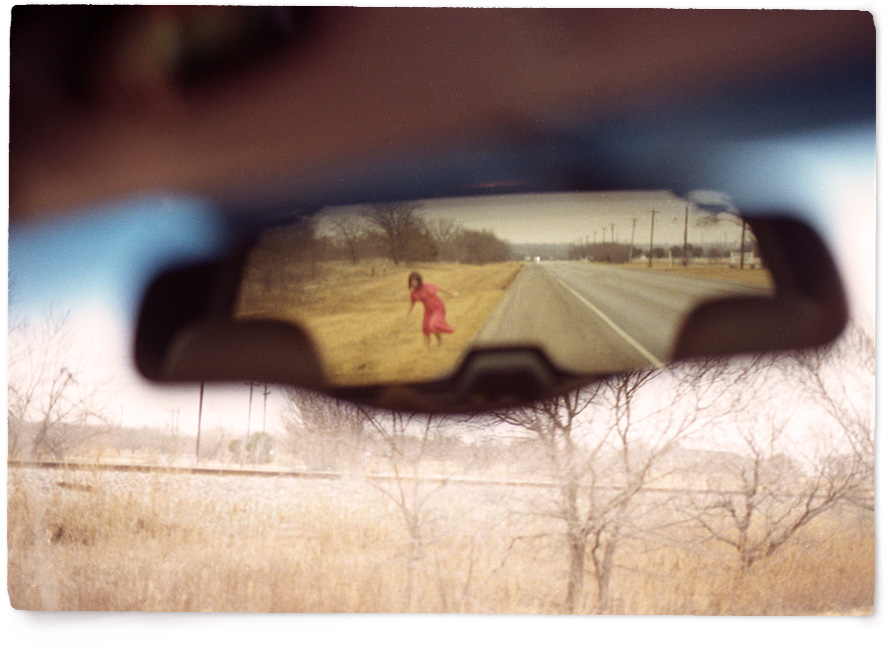

The time following Bret’s death left me questioning my own mortality. The earth still turned, and time went on; however, I was truly struggling. I decided to turn my camera on myself, capturing a series of self-portraits entitled, Haunting. As uncomfortable as I felt in front of my own camera, I explored different vantage points, studio verses natural lighting, and creative elements such as a water-soaked piece of plexiglass (set between the camera and myself). One day, I found a roll of gauze and, for some reason, decided to place it over my head and face. It was this capture that reminded me of my father and his work. After submitting this self-portrait for a class assignment, I received positive feedback from both my professor and peers. The most significant response was to “keep digging.”

Haunting | Dianne Morton | 2015

As I journaled, I reflected on memories from my childhood, especially those involving my father who worked as a mortician and deputy coroner. I was used to our phone ringing at all hours. If there was a car accident, house fire, suicide, or the like, my father was called to make the “removal.”

My earliest memories of the mortuary included the family business’ signature blue pencils, which I kept in a plastic case in my wooden school desk.

Over time, my father became quite well known in the community, not only because he buried many people in town but also for his kindheartedness. When I was in first grade, our teacher asked the class what each of our fathers did for work. I raised my hand to answer, “My dad makes blue pencils.” I proceeded to proudly hold up my blue pencil, which had my last name printed on it with the label “Sneider & Sullivan Funeral Home.”

It wasn’t until the following year, second grade, that I began to understand how my father truly spent his time at work. It as the day I learned that the boy who sat in front of me, Jimmy Alden, died over the weekend. A car had hit Jimmy. After the morning school bell rang, our second-grade teacher briefly explained to our class that Jimmy was in Heaven.

Our class attended Jimmy’s funeral and there, standing next to his white casket, was my father.

While working on my photographs, I found the inspiration to combine three distinct artistic genres (portraiture, self-portraiture, and still-life) as a means to build my autobiographical series, Blue Pencils. My intent is to communicate my intimate childhood memories as the young daughter of a mortician. My unique experience translates to pictorial storytelling, allowing the viewer to see something that may appear vague or ethereal.

Resources

[1] Nichols, T. Artistic Motivation: Examining Motivation. Module 5. PH810-OL1: Concept & Image. Academy of Art University. Web. 10 March 2018.